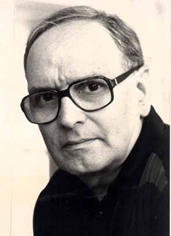

Ennio Morricone’s production includes music for many different kinds of theatrical performance – for the theatre, for clubs and cabaret, for radio and for television. Indeed he has been involved with television right from the very first Italian TV broadcast on January 3, 1954 to recent large-scale productions such as Mosè, Marco Polo, La Piovra and I Promessi sposi. He has also made crucial contributions to the Italian recording industry from its very beginning and it was he who created the role of the arranger as a vital figure, and he has given many singers and song-writers the help which was to prove a decisive factor in the successes they subsequent1y enjoyed. The fírst film to include his name on its credits was Il Federale by Luciano Salce, and Morricone’s name soon became closely linked in important artistic partnerships with Italian directors such as Leone, Petri, Pontecorvo, Bolognini, Bellocchio, Pasolini, Montaldo and Tornatore, and abroad with Polansky, De Pa1ma, Joffé, Lautner, Carpenter and Molinaro, and more recently with Rosi, Almodovar and Zeffirelli. In addition to the stunning quantity of film music (nearly 280 scores) and the many smaller scale works for other sectors of show business, Morricone has kept up an almost continuous production of music for the concert hall. In the early years he kept these two different areas of activity completely separate, but since his involvement in the 70's with the experimental “Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza”, he has started to imperceptibly merge the two areas in his research for a visionary language of synthesis. Over the last ten years or so there has been an appreciable increase in his output of music for concert performance, and the catalogue of his published works now includes over 50 compositions. There are pieces for solo instruments (guitar, piano, harpsichord, cello, viola and tape, and flute and tape) and for a variety of chamber group combinations (trios, quintets, sextets, mixed ensemble with piano, for voice and piano, voice and instrumental group, and unaccompanied choir). Large scale compositions include the polyglot cantata Frammenti di Eros (1985) with texts by Sergio Miceli, and the Cantata per l’Europa (1988) with texts by various authors; three Concertos: for orchestra (1957), for flute and cello (1985) and for amplified classical guitar and marimba (1991); the ballet music Requiem per un Destino (1966) and Gestazíone (1980); and a variety of pieces for voices and instruments either based on religious themes or religiously inspired such as Quattro Anamorfosi latine (1990) and Una Via Crucis (1991-92) both on texts by Miceli. Morricone was born on November 10, 1928 in a well-known quarter in the centre of Rome called Trastevere. His father, Mario, was a noted trumpeter who worked in several light music orchestras, while his mother, Libera Ridolfi, in later years set up a small textile business. It is probable that Morricone grew up in a typical working-class family atmosphere, where work and daily life were híghly inter-dependent and characterised by a dignified work ethic. Morricone was not just musically precocious – he wrote his first compositions when he was only six – but he was deliberately encouraged to develop these natural talents and he was given a training that would prepare him to take over his father's roles both at home and at work. The Morricone family was guided by a down-to-earth spirit which would have encouraged the son to follow in his father's footsteps no matter what his talents were, but having these innate talents must have made accepting this family destiny much more palatable. Because Mario Morricone worked in so-called non-academic circles and because of then prevailing atmosphere, in the war years it was much easier to learn and practice a trade without going through formal training. Indeed there were many such talented but unqualified musicians in the ranks of many ensembles and orchestras at that time. However, Morricone's talents and interests led him to simultaneously follow two conflicting paths: he enrolled at the Music Conservatory to study trumpet with Umberto Semproni and Reginaldo Caffarelli, yet at only 14 years of age he found himself having to stand in for his father who had fallen ill. At night he worked as a young "colt” in Costantino Ferri’s Light Orchestra, and by day he studied harmony with Roberto Caggiano at the Santa Cecilia Conservatory. Caggiano was the first person to recognise Morricone’s talents and to suggest that he also study composition. During the ten years after the end of the war, Morricone continued to straddle the conflicting paths of his early musical development. Just like any other young composer from a humble family, he was full of lofty ideals, wishing to prove his worth by setting challenging texts to music. Between 1946 and 1950 he wrote six (unpublished) Lieder for voice and piano: Distacco I (words by R. Gnoli); Imitazione (words by G. Leopardi, dated 27.11.1947); Distacco Il (words by Gnoli), Oboe Sommerso (words by S. Quasimodo); Verrà la morte (words by C. Pavese) and Intimità (words by 0. Dini). Between these pieces, “Imitazione” and “Verrà la morte” stand out for their unabashed and compelling lyricism. Self-effacing yet pragmatic, canny yet sincere – these are the personality traits that made Morricone the man and musician he is. His teachers (Carlo Giorgio Garofalo, Alfredo De Ninno, Antonio Ferdinandi and Goffredo Petrassi with whom he got his diploma in 1956) often didn’t know what he was up to outside of their lessons: he played in a light music orchestra; at the Teatro Eliseo he played in the off-stage band of Renzo Ricci and Eva Magni's Shakespeare season, for which he was also later asked to write some brief interludes for trumpet and percussion. This may well have been his first commissioned work. During 1953 and 1954, along with Firmino Sinfonia, Aldo Clementi, Domenico Guaccero and Boris Porena, he followed Petrassi’s composition class for which he composed a Sonata for Brass, Timpani and Piano (one of the first pieces he still acknowledges). In the same period he was put in touch with Gorny Kramer and Lelio Luttazzi who asked him to arrange some medleys in an American style for a radio broadcast they were preparing. This was Morricone’s first job in what was to become a fervent but clandestine career as an arranger. At the Conservatory he also took courses in choral music, choir conducting, and in wind band arrangements. Just as he was coming to the end of his studies he began to get work as an arranger for the principal light music orchestras of the RAI Television, working in particular with Armando Trovajoli and Carlo Savina. This and other work with the RAI led to his involvement in the first successful post-war radio broadcasts and with the birth of television, including such historic programmes as Gente che va, gente che viene, Il Giornalaccio and Studio 1. Around this time Morricone also won a contract with RCA Italiana and soon became a key figure in the rapidly expanding Italian recording industry, distinguishing himself for his originality and contemporary style. An excellent example is the beautiful arrangements he wrote for the singer Miranda Martino, which are full of ironic allusions to classical music. In fact his contributions to both the recording industry and to television and film have been so far reaching that in any hypothetical analysis of the history of the relationship between music and the mass-media, Morricone would undoubtedly emerge as one of its most symbolic and all-embracing figures. A glance at the list of works written between 1954 and 1959 shows that the eclecticism found in his light music is equally pervasive in his other work. In this period he wrote a host of chamber and orchestral pieces: Musica per archi e pianoforte (1954); Invenzione, Canone e Ricercare for piano; Sestetto for flute, oboe, bassoon, violin, viola and cello (1955); Dodici Variazioni for oboe d’amore, cello and piano; Trio for clarinet, horn and cello; Variazioni su un tema di Frescobaldi (1956); Quattro pezzi per chitarra (1957); Distanze for violin, cello and piano; Musica per undici violini; Tre Studi for flute, clarinet and bassoon (1958); and the Concerto per orchestra (1957, dedicated to Petrassi). Unfortunately the pressure of work on other fronts led to a major hiatus in his composition of music for the concert hall. Up until the late 60’s there had always been a seemingly unbridgeable divide between his commercial and non commercial music. Yet in the following decade new elements began to emerge in his work, symbolising an attempt to bridge this gap. He drastically curtailed his work as an arranger, and works such as the Requiem per un Destino (1966) and the Caput coctu show (written in 1967 on a difficult text by Pier Paolo Pasolini) reveal a forward looking if not strictly linear development. This evolution continues progressively through Da molto lontano (1969) for soprano and five instruments, Suoni per Dino for viola and two tape recorders, to Immobile (1978). Furthermore a few pieces originally written in the mid 60’s for the cinema were rewritten to be performed as concert pieces, and several other pieces originally intended for the concert hall were reworked as film scores. This is not a merely casual recycling of ideas and materials of the type commonly exploited by composers in the past, for if we look at the music for Pasolini’s “Teorema” or for Petri’s “Un tranquillo posto di campagna” (both made in 1968) we find that for these films Morricone’s style has radically changed and that this music has been written in a severely contemporary idiom. In fact, in these films the directors themselves expressly desired to work “without compromising” and it was this statement of intent which allowed Morricone to move away from his usual role of the skilled craftsman. It is highly significant that the music for these films is remarkably similar in style to the other music he was writing at that time. It is a music which tends to be austerely programmatic, sometimes so much so that it would seem to be a deliberate act of self-chastisement. With works of the quality of Grande violino piccolo bambino and Bambini del Mondo (both written in 1979) Morricone entered his best period, a period characterised by such serenely joyful and inventive pieces as Tre Scioperi (written between 1975 and 1988 on texts by Pasolini) for a class of thirty-six school-children and bass drum; Frammenti di giochi (1990) for cello and harp; Ut (1991) for trumpet in C, timpani, bass drum and string orchestra; off-set by other pieces of scathing irony such as Epitaffi sparsi (written in 1991-92 on texts by Miceli) for soprano and piano. For more information please go to the composer's website: Click here |

|

|

|

|

Ennio Morricone - Composer Information

Search our Library

Featured Composers

Counterpoint Music Library Services

Copyright © 2012 All Rights Reserved

Copyright © 2012 All Rights Reserved

Created by Wavelength Media